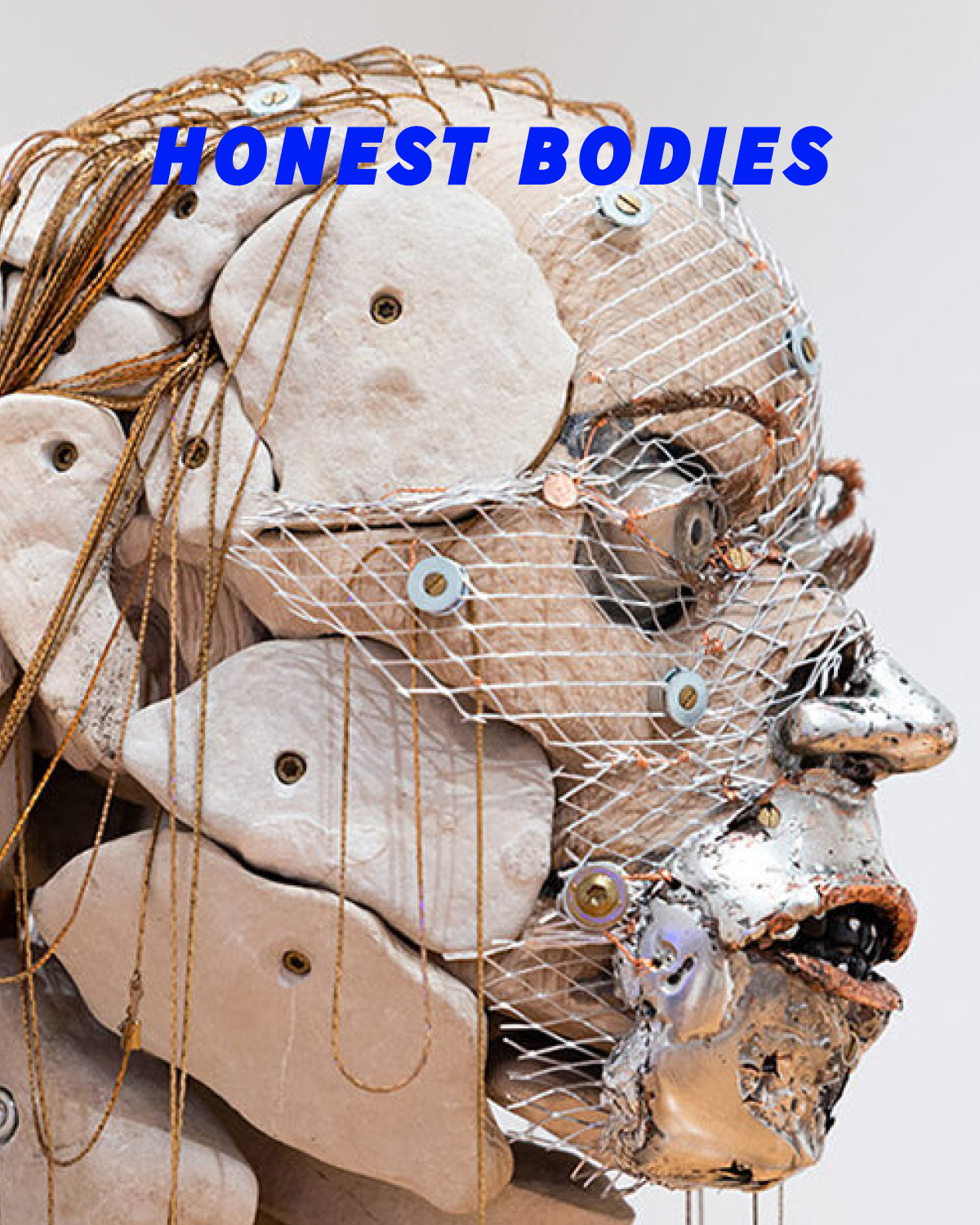

Honest Bodies

2.12.2022- 3.27.2022

“Sure there's temptations to jump into the quicksand and disappear myself for the easy and rote approval of instant validation, but that will soon dry up and evaporate. What is eternal I think, is a relationship to a kind of beauty that shifts alongside you. My hope is that when I'm 70, and 80, and 90 and 100, I can look at my skin and still find it beautiful because it's honest to what I am at those ages, my hope is that increasingly, I become comfortable with the creases under my eyes, around my lips, because they're honest, they're markers of what it means for me to have lived. My hope is that the “discolorations” won't be seen as discoloration, they will just be seen as variations in my skin tone, which are honest, because I'm not sleeping, my hope is that we don't have to lie and pretend about the collateral weight that capitalism has on our bodies that of course, we're exhausted, and it shouldn't be my responsibility to conceal that exhaustion, I should be able to say I am exhausted. I guess it’s just honest bodies and that's always what motivated me in fact.” — Alok Vaid-Menon

Our bodies follow material pathways. As we experience a shifting material landscape through the conditions of this pandemic, mortality and death are made visible as stages of a material process. Death, as a final teleological event, is a material process that is often garnished by ritual and ceremony. Our bodies, decorated in their final moments, are vessels for projected human visions of utopia; their ornament indicates a final conquest to be experienced by the body without organs in landscapes of the sublime.

Bodies are subject to the same modes of existence as all objects–a banal series of values and crossings that determine position and context. Subject to laws and nature, the body as an object is incorrectly distinguished by its desires. Desires appear to be independent actors within these wheels of commerce, but they too are affected by the same forms of manipulation characterized by any repressive desublimation. Our society of repression favors instantaneous pleasure and diminishes our ability to have social critique. Is it possible to have an honest body?

“This was a low year, a year spent looking at the ground, a year spent walking, outdoors, alone or with others, spent looking at the sidewalk, at the things people were throwing away. This was a year spent trying to find the value in the least of what we had, of what we had been taking for granted. This was a year I spent collecting every scrap of ‘worthless’ thing I found on the street, large or small, in the New York City neighborhoods where I live and work. This was a year I also spent visiting every major cemetery in the five boroughs, cataloging and collecting the ways we’ve used representations of our bodies in stone and arrangements of objects to describe our grief. This was a year I also spent digging in the ground at various informal and accidental archeological sites across the city - from dead horse bay to municipal construction sites after-hours – to collect what fragmentary material history of our city remains beneath us in the ground. All these things are ‘low’ things, things we put in or on the ground. They are in many ways the least of what we have, as a city, and they are the only things this work is made from.” — Taylor Baldwin

How should we celebrate our bodies as material; as a part of the architectonic skin of all objects in motion? This naked planet does not care if we die. Nor does this society of repression provide answers to questions of existence as it relates to commerce and circulation. For if it did, the repressed society would reveal its determination to control for the sake of its own survival and motion.

Serra Victoria Bothwell Fels and Taylor Baldwin propose that physical material is not a skin, but rather a forever-changing representation of our history. The ground quite literally is a formulary for understanding past desires and, thereby, is foundational to understanding the material conditions that shape our thoughts and visions. To transgress the conditions of a capitalistic outgrowth, the body must remain aware of the architectural parameters that define its containment.

“Natural ecosystems evolve through organisms changing themselves to exploit unoccupied niches within an environment, creating opportunities for their own growth. I approach the constructed environments we occupy in much the same way. My installations of architectural opportunism investigate the pockets of architectural landscapes that are underutilized, unoccupied, and can make space for a shift in perception. I manipulate and adapt existing structures, making surrealist outbreaks that merge and confound our expectations of body, of place, of being.” — Serra Victoria Bothwell Fels

By manipulating the landscape, Fels and Baldwin call attention to the processes in which the ground distorts our understanding of space. On this inclining promenade, Fels and Baldwin present distorted bodies created with a debased understanding of material normatives. Figures with skins of cultural refuse stand as altars asunder a drop ceiling, which in its own movement sags toward the ground as if in a gravitational escape from the geometric order that supports it. This ecosystem, like a knife in the water, transgresses a pacified habituation of space and all of its conditional manipulations.

This project was supported, in part, by a Foundation for Contemporary Arts Emergency Grant.

Taylor Baldwin (b. tucson, az 1983) is an artist working primarily in sculpture, video, and installation. he received a bfa from rhode island school of design in 2005 and an mfa from virginia commonwealth university in 2007. he has been a resident at the skowhegan school of painting and sculpture, the fine arts work center, the bemis center for contemporary art, and the seven below arts initiative.

Baldwin has exhibited individually at wayfarers gallery (brooklyn, ny) conner contemporary gallery (washington d.c.) , land of tomorrow gallery (louisville, ky), and vox populi (philadelphia, pa) as well as groups shows at the queens museum of art (queens, ny), tucson museum of contemporary art (tucson, az), the virginia museum of contemporary art (norfolk, va), the kentucky museum of arts and craft (louisville, ky) and zürcher gallery (manhatten, ny). he is currently based in queens, new york and providence, rhode island.

Serra Victoria Bothwell Fels (b. Knoxville, TN) works in site-responsive sculptural installations embedded into pre-existing architectural contexts. Her sculptural interventions and outcroppings transform mundane architectural features into sites of imaginative disruption, unexpectedly shifting our sense of reality, and revealing the significant role our environment plays in our perceptions of being.

Initially trained as a social psychologist at Stanford University, then as a metalsmith at the Appalachian Center for Craft, Bothwell Fels received her MFA from Columbia University. Her work has been presented at the Palais de Tokyo (Paris), The Clocktower Gallery (NYC), Pioneer Works (Brooklyn), University of Wisconsin (Oshkosh), BRIC (Brooklyn), Sun Valley Center for the Arts (Ketchum), and Smack Mellon (Brooklyn). She is the recipient of a Peter S. Reed Foundation Award, Purchase College’s Windgate Fellowship, and a 2019 NYFA Architecture/Environmental Structure/Design Finalist.