Detour: cul-de-sac

10.9.2022 – 12.11.2022

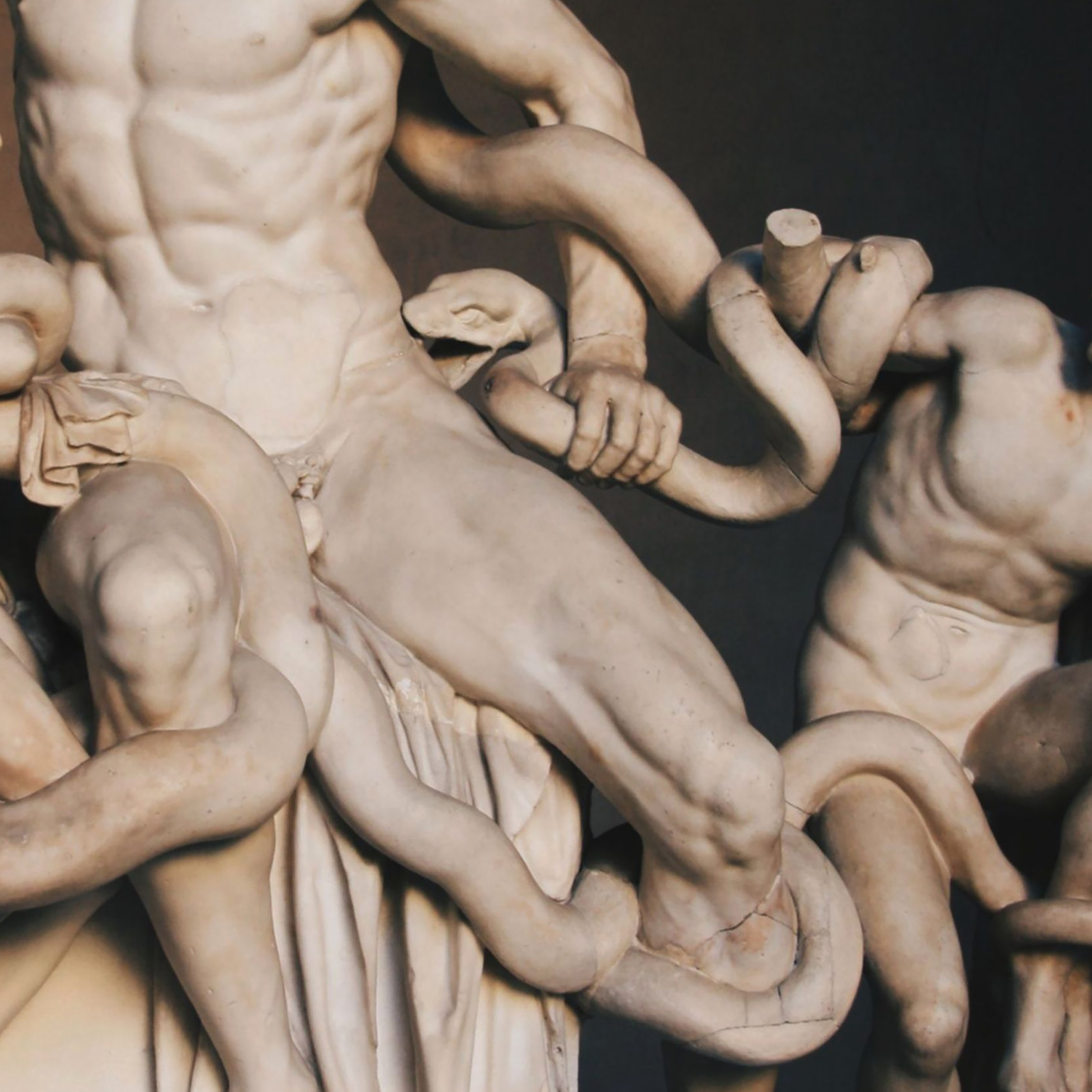

Laocoön and his sons, excavated in Rome in 1506, marble

“Any elements, no matter where they are taken from, can be used to make new combinations. The discoveries of modern poetry regarding the analogical structure of images demonstrate that when two objects are brought together, no matter how far apart their original contexts may be, a relationship is always formed. Restricting oneself to a personal arrangement of words is mere convention. The mutual interference of two worlds of feeling, or the juxtaposition of two independent expressions, supersedes the original elements and produces a synthetic organization of greater efficacy. Anything can be used… It is thus necessary to envisage a parodic-serious stage where the accumulation of détourned elements, far from aiming to arouse indignation or laughter by alluding to some original work, will express our indifference toward a meaningless and forgotten original, and concern itself with rendering a certain sublimity.”

—Guy Debord, Gil J Wolman, A User’s Guide to Détournement, 1956.

A series of linear pathways standing against an inclining gallery floor support a range of disembodied arms and sleeves rendered in marble and fabric. In this architectural composition, Chang Sujung and Chris Domenick suggest that containers, both objects and bodies, are often tools of deception; designed to confuse or manipulate the nature of their contents. In a poetics of détournement, Chang and Domenick explore the conditional impact of sign-systems on bodies by creating a fantasy of transgression in altered forms.

The human body is a highly organized container. It’s design contains internal pathways that allow for the mobility of unique cells and organs to accomplish the specific functions for sustaining life. Externally, a human body in motion follows material pathways. Material pathways, described by lines and direction, are also contained environments that organize the surrounding landscape, allowing for the mobility of bodies and acting as a carrier for the innumerable objects in circulation. The movement of bodies reflects the movements of their contents just as the architecture of material pathways gives image to bodies and objects in motion. The material pathway, much like the body, is a system with defined parameters.

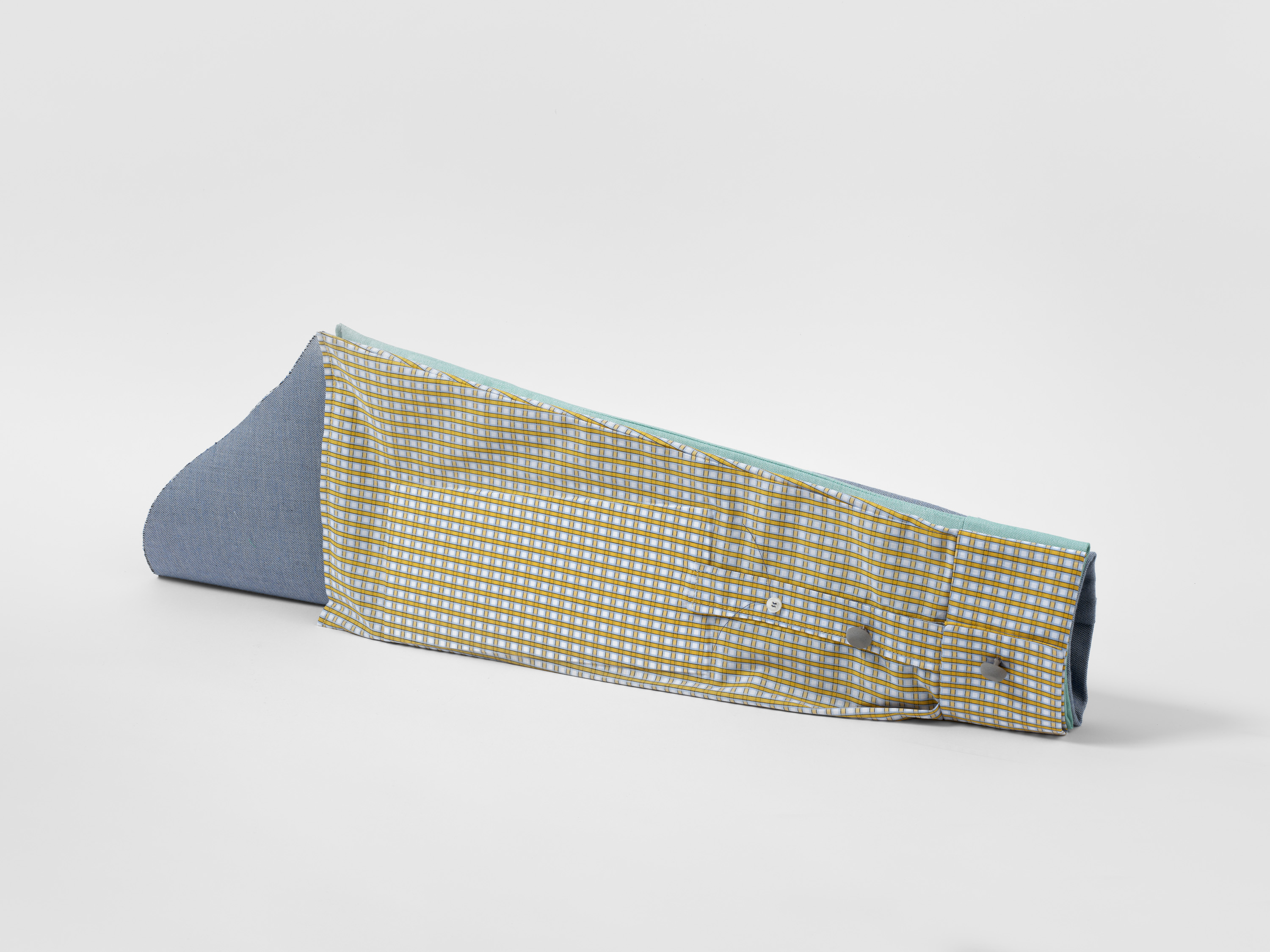

Chang Sujung reminds us of the similarities of bodies and material in motion in her statement relating the sleeve of a shirt to it’s contents:

“I am interested in sleeves as a carrier. It is a container for a human arm, tricks, objects, and what we believe as truth. The sleeve is directly correlated to deception and truth in the Korean equivalent of pickpocketing. Translated to ‘pick-sleeving’, the Korean idiom refers to the sleeve as being a place where you keep invaluable things in Korean traditional clothing. So, in the past, a pickpocketer in Korea would not seek their target from within your pockets; rather they would steal from your sleeve, the ‘carrier’ of your items… I make sleeves without a torso, therefore they lose their commodity value as articles of fashion. In doing so, my sleeves become independent objects, as a casing or carrier. Considering also that to ‘wear one’s heart on one’s sleeves’ means to openly show one’s feeling or emotions, and thus to allow oneself to be vulnerable, I cannot help myself from thinking about the entangled relationship between the sleeve and being truthful.”

The sleeve in this sense is a deceptor, insulating the arm from it’s surroundings and concealing what it serves to protect. This deception acts with a double, mythological function: bodies and material adorned with ornament, relate themselves to the processes by which they should be desired or consumed. Simultaneously, this trickery conceals the processes that brought them into existence; their labor, construction and their propensity to reproduce.

With a series of elevated platforms, Domenick reformulates the language of material pathways with architectural collage and vernacular construction. As literal carriers, Domenick’s linear surfaces are less deceptive; their form and content reach a synthesis aligned with an aesthetic mode of existence. Coated with the gestural marks of abstract painting, they act as propositional signifiers, characterized by the infrastructural nature of a built environment, but also with an alterity suggesting that the environment was only recreated though a memory of it’s organization. Without illusion, Domenick’s pathways render an organized environment through a disordered language that questions the arrangement of signs and images and their impact on the movements of the objects and bodies they contain.

By stripping the natural environment of it’s own organization, material pathways can be seen as deceptive authorities, controlling mechanisms that suppress their occupants. The coercions that are acted upon the body serve to mechanize its behavior. The body in motion remains disciplined; even with an increased utility it’s containment forces it into docility. By organizing bodies, material pathways establish a power over them. Under constant subjection, the body and object contained act upon their contents as their container acts upon them.

As this composition of works by Chang and Domenick may create ontological confusion as a system, it also serves through alterity to illuminate a material world that is deceiving our bodies by controlling their movements and manipulating their desires. Although we can scarcely discern these mechanisms of control, by working against them and altering them, a countermovement begins, and ultimately leads to demystifying others.

Chang Sujung, WE’RE HAPPY, 2022